The words ‘Garden’ and ‘Painting’ put together remind us of the works of French artist Claude Monet and his impressionist paintings such as ‘Waterlily-pond’ or ‘Women in Garden. Yet, The Garden Project by Kerry James Marshall makes a resonating dent in how one looks at art. The idea of a Garden in a painting usually relates to hope, recreation, and aesthetics. Somehow the Garden Project veers away from the social construct of a garden and culminates in a narrative that represents the complexities of life in low-income housing projects. Ironically, all housing projects portrayed in his project bear the name of a Garden.

Art history shows that artists prefer to paint light-skinned subjects in their paintings. However, in his paintings, Marshall breaks this norm and primarily paints African American subjects, trying to fit in a world that has always been biased. In the Met collect interview, Marshall explains1 , “When you are on the outside, you have to prove that you belong in there.” With his new style of painting portraits, he has made his place in history. His paintings are a fitting example of belonging, as they make way for a new genre of artists who can now imagine contemporary art with black subjects.

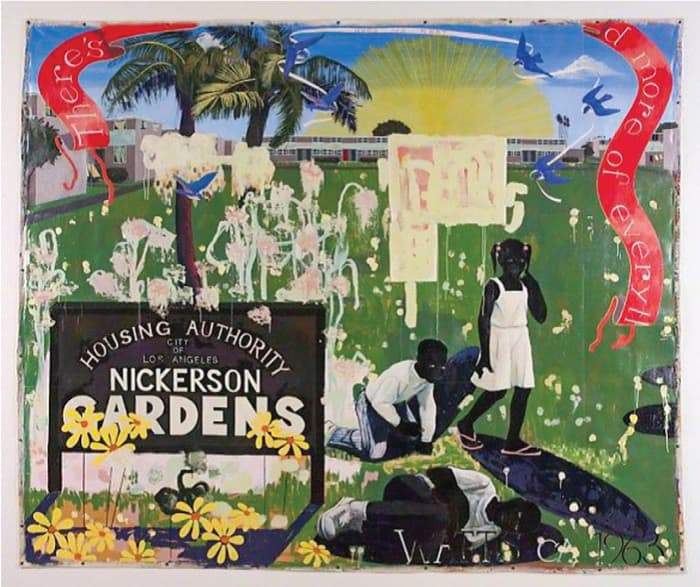

In his painting titled ‘Watts,’ Marshall depicts a scene from his childhood in 1963 at the age of eight with his brother and sister playing in the Garden of the Housing project named Nickerson Gardens. The sign sitting at the bottom of the painting clearly identifies the housing authority project. The sun’s rays rising above the buildings light up the Garden with hope in the background. The Garden looks more like a sports field than a garden with its rectangular shape, and the buildings surround the Garden like a protective boundary with pavements moving in and out of the buildings. Marshall and his siblings seem to be playing in the Garden surrounded by Palm trees. The Bluebirds of happiness hold a ribbon that reads Alabama’s first state Motto, ‘Here we Rest.’ The title Watts CA 1963 hides neatly into the painting in the bottom left.

Watts, at first glance, can be read like an advertisement of a utopian neighborhood, a place with a promise of a glorious future. However, the project shown like a paradise is surrounded by a dark cloud of violence, segregation, and discrimination. The scribbled-out boxes give an impression of someone trying to speak, but the voices are suppressed under the brush strokes, depicting the everyday struggles of housing projects.

The paintings of landscapes by great artists like Monet primarily focus on the scenes of daily lives, seldom with a social message. Marshalls Paintings juxtapose this thought process and send a resounding social message of a marginalized community.

Article written as a part of Proseminar Fall 2021 Pratt MSUD